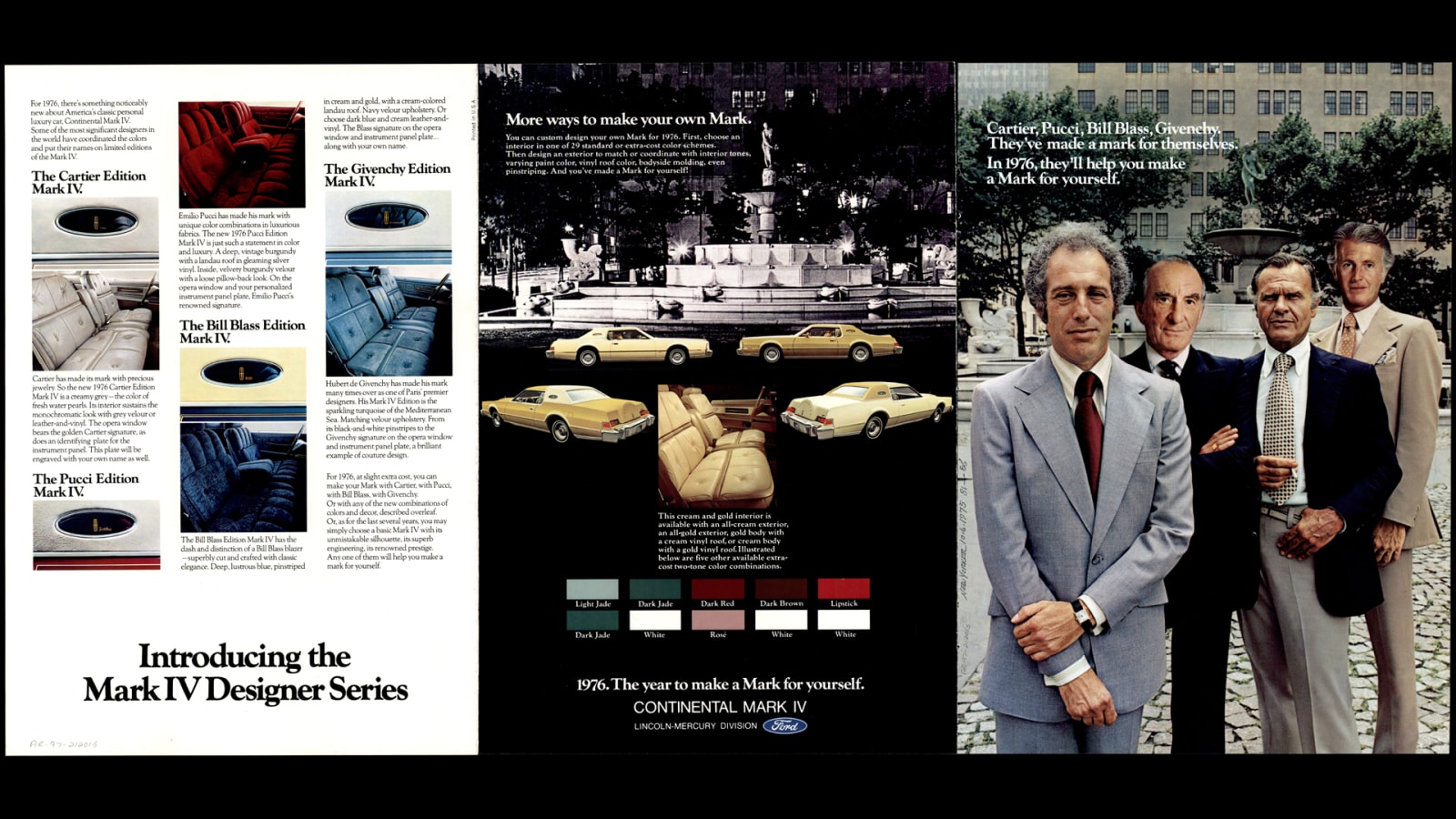

The Lincoln Designer Series was introduced in 1976, at the end of the imposing Mark IV Continental generation. Four big-name fashion designers of the era – all-American country clubber Bill Blass, psychedelic Italian pattern-maestro Emilio Pucci, venerable French jewelry-maker Cartier, and à la mode French fashionista Hubert de Givenchy – were asked to slather their elegance on Lincoln’s personal luxury coupe.

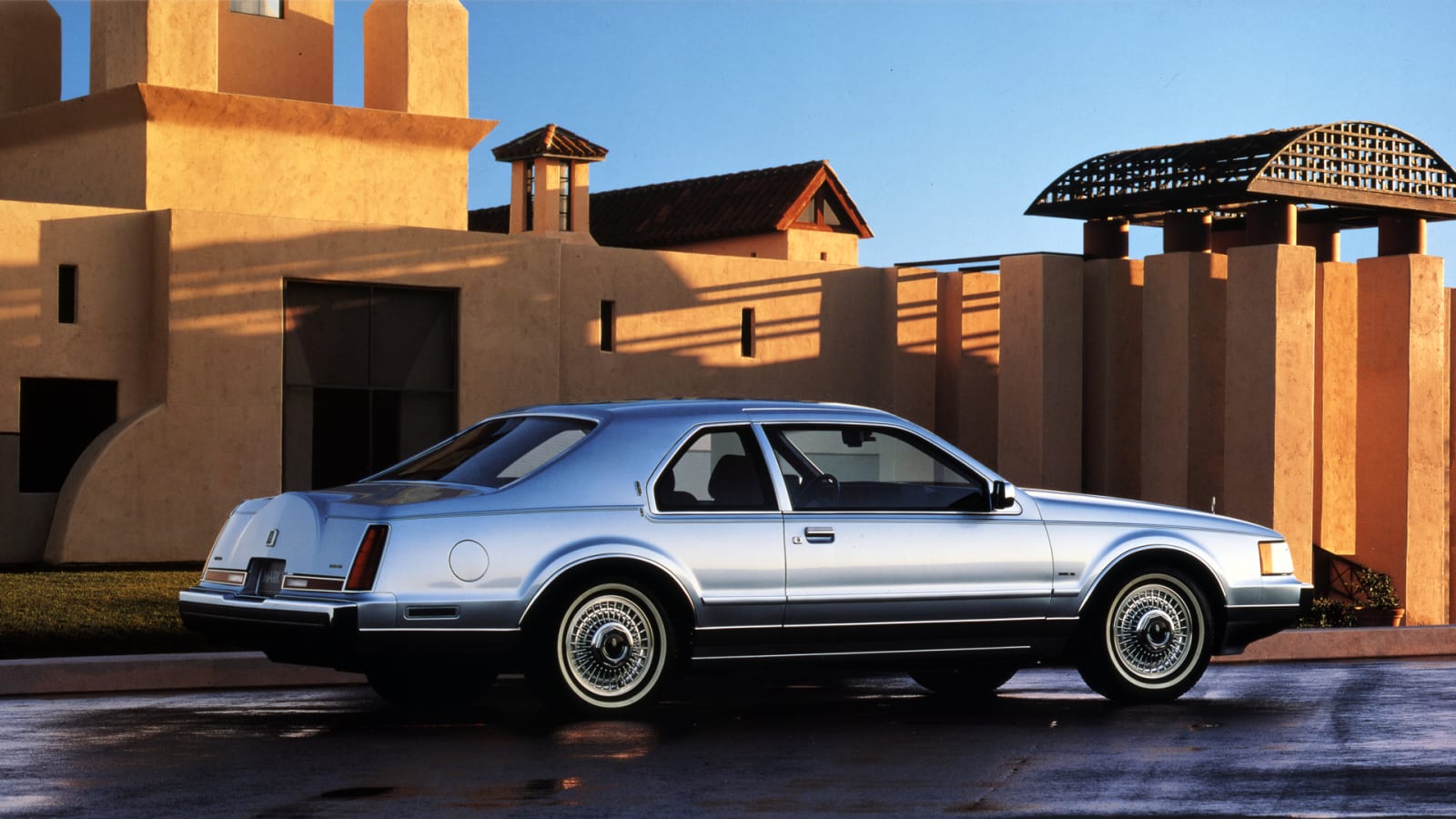

This experiment was a wild success. According to documents uncovered in the Lincoln archives – with the incomparable guidance of official brand historian Ted Ryan – the Designer series “accounted for more than 27% of Mark IV sales” shortly after its introduction. It was such a runaway hit, that it continued on throughout the even larger Mark V generation (incidentally, the longest coupe ever produced by Ford Motor Company), and didn’t really peter out on these big two-doors until the early 1990s.

But the true history of the series well predates the era of opera windows, crushed velour and wire wheel covers.

“If you take a step back even further, when Ford purchased Lincoln in 1922, Edsel Ford was put in charge of the company. But more than that, he helped establish the first design studio at Ford,” said Ryan. The basic Model T didn’t take much design. Lincoln was different. Edsel is famed for his quote. “Father wanted to make the most popular car, I wanted to make the best.”

The specific genesis of the Designer Series, however, came along as a result of a long-term personal connection with the marque’s first chairman. “Edsel Ford had a relationship with Cartier, and correspondence going throughout the 1920s and ’30s,” Ryan said. “His personal cards and stationery were always ordered from Cartier.”

This enduring link wasn’t formalized until the late 1960s. “I found in product development files, in 1967, that Ford had gone to Cartier for a special 1970 Cartier Continental coupe,” Ryan said. According to internal documents, this package would include unique interior leather/cloth/vinyl surfaces and trim, modified dials, and a Cartier jewelry box, as well as golden plating on the steering wheel ornament, dial face ornaments, keys, C-pillar ornaments, door monograms, and dashboard plaque.

“Think of that. A car that never was, that could have been,” Ryan said, wistfully.

Some Cartier magic did get glossed on Lincolns in the late 1960s. A Cartier-branded dashboard clock originated in the Lincoln Mark III for 1969, and continued to be available on the Mark IV before the launch of the Designer Series.

The final impetus for the series came from an even more unlikely source.

“The idea for the involvement of outside designers originated in 1974 with a Mustang program called ‘Fashions N’ Wheels’,” said Ryan. This concept involved Bill Blass designing clothing and accessories that would be sold alongside the then-new Mustang II. “This idea was a big success, leading management to consider how to expand it,” Ryan added.

The idea went all the way up the chain of command, to company president Lee Iacocca.

“We don’t have the pitch deck that went to Iacocca, I just have something that says, Lee Iacocca approved, on this date, this particular program,” Ryan said.

In order to give the series’ models specificity, and keep them fresh as they changed year-over-year, the designers or their representatives came to Ford headquarters in Dearborn, Michigan, annually, for a festival of fabric and trim swatches, creative meetings, concept approvals, and wining and dining. Paint and interior colors and materials shifted annually. Ultimately, this process became a signpost, an event, in the Motor City.

“The introduction of each new designer edition became something like a fashion line being premiered in Paris or New York,” said Ryan.

However, the changes were sometimes less than thrilling. “We have product planning committee minutes, which are dry as toast. It just reads, Representatives from XYX designers came to Dearborn and selected colors. Changes made include this, this, and this. The level of humor and fun is difficult to discern.” Ryan said. “In one of the Bill Blass ones, he said that he wanted to just add a red stripe on the back of the rearview mirror.”

The Designer Series continued nearly throughout the end of the Mark coupe range, dying out only with the introduction of the final Mark VIII, in the early 1990s. Gleefully, before it ran its course, the scion of overwhelming Italian opulence, Gianni Versace, got a turn for two years in the mid-1980s. But by the end of the Mark VII, and the series, only Bill Blass was keeping the design embers glowing.

Less clear is why exactly the program came to an end. “We don’t really know now why it ended. We don’t have any documentation on that. I speculate that it just ran its course. Every good car line runs its course,” said Ryan.

Other fashion brands – including Ermenegildo Zegna, Thom Browne and Zac Posen, John Varvatos, Isaac Mizrahi, and KITH – have, in recent years, experimented in automotive cross-branding. And it could be argued that AMC predated Ford with its Levi’s, Pierre Cardin, and Gucci editions in the early-to-mid 1970s. But AMC is long gone, sadly, and never came close to hitting the 100-year mark.

The practice remains a distinguishing feature of Lincoln during its century-long automotive reign, and one that aligns with the brand’s foundational mythologies. Edsel Ford was the one who brought in Diego Rivera to Detroit to create the Detroit Industry murals at the Detroit Institute of Arts. He was a designer, and art lover, at heart.

“The DNA of Lincoln was always such that a designer series would have matched it, and matched Edsel’s vision for what Lincoln was and could be,” Ryan said. “He would be smiling to know that his company had played this role.”

Source: www.autoblog.com