It has been over a year since I pieced together a Ford Bronco speculative suspension deep dive using preliminary specifications, comparisons to the overseas-market Ranger Raptor, and teaser photos of a naked chassis. Today the specs are more complete, and I’ve been able to lay my hands on the real thing for a closer look in my own driveway. The two-door body may be bolted in place this time, but I’ll take that because I’m able to remove the tires and poke around underneath.

This Bronco is a two-door First Edition, a 2021 trim level that’s sold out. You can basically ignore that fact, because everything it included can be still found on the 2022 Ford Bronco Badlands. Importantly, it also has everything we’d care to look at as far as a suspension deep dive is concerned, plus more. It had the stabilizer bar disconnect mechanism shared with the Badlands, locking front and rear differentials that are common to the Badlands and the Wildtrak, and the Sasquatch combination of HOSS Bilstein dampers and 35-inch tires that comes standard on Wildtrak and can be added to any trim as an option.

The Bronco I prefer is the Badlands, which has everything we’ll see here, but with 33-inch tires paired with a longer-travel set of HOSS Bilstein dampers. The reason? The 33s don’t stuff the wheel wells as much as this 35-inch rubber, and as a result, they allow for greater flex and articulation. This setup, with the 35s, managed a 648-point maximum Flex Index score on my RTI ramp (see video above), but a Badlands without Sasquatch would do even better.

Most of the Bronco vs Wrangler trash talk centers on the Bronco’s use of independent front suspension. Jeep people will say, “Solid front axles flex more.” They’re not wrong, but solid axles don’t ride smoothly or steer accurately when you’re not off-roading, and they’re not nearly as settled on washboard dirt roads. Unless the need for maximum articulation enters the frame, independent front suspension and the lower unsprung mass that comes with it can be a better way to go if that suspension offers decent ground clearance and a healthy amount of travel.

The suspension we see here is not a direct carryover from the North American Ford Ranger pickup we know. Instead it comes from the Ranger Raptor sold in Australia, Europe and other parts of the world. As the Raptor name implies, it’s a wide-track, long-travel independent front suspension. Rumors of a U.S. Bronco Raptor will no doubt build up from what we’ll see here.

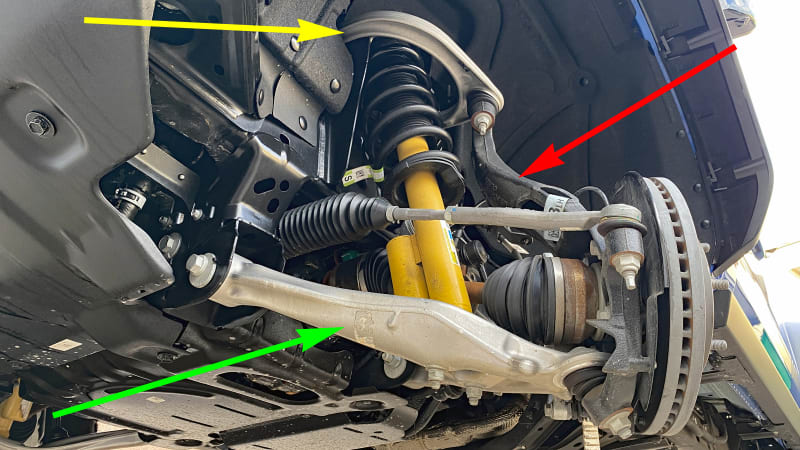

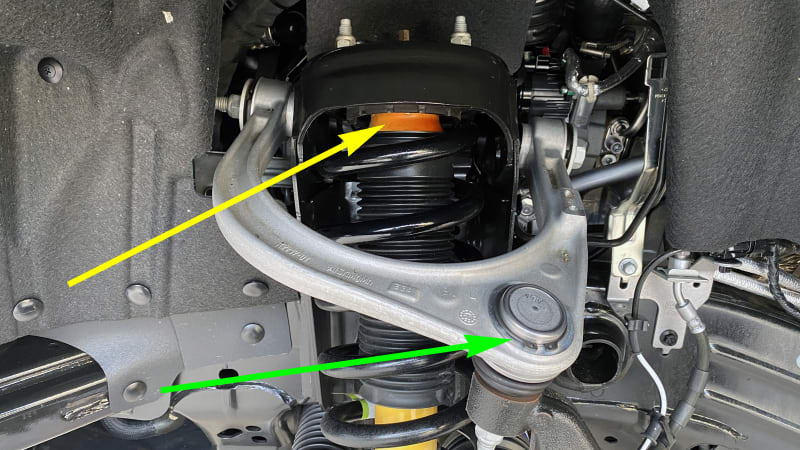

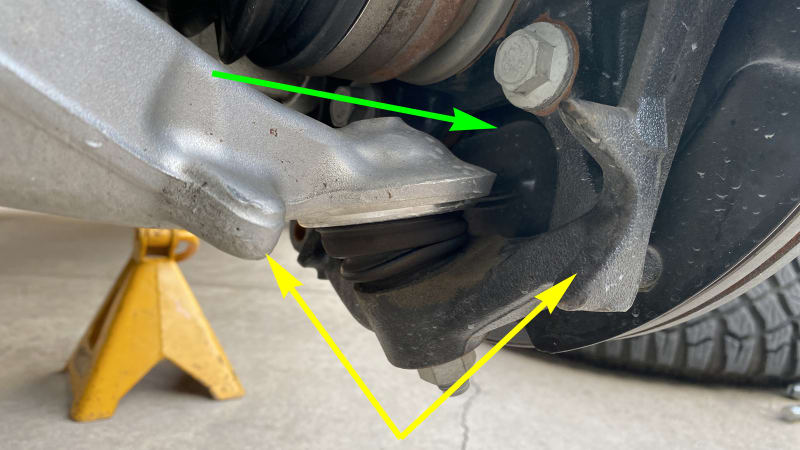

It’s clearly a double wishbone front suspension, with upper (yellow) and lower (green) wishbones made of aluminum, and a steering knuckle (red) that’s made of steel. This combination is a direct opposite of the North American Ranger pickup, which uses steel arms and an aluminum knuckle.

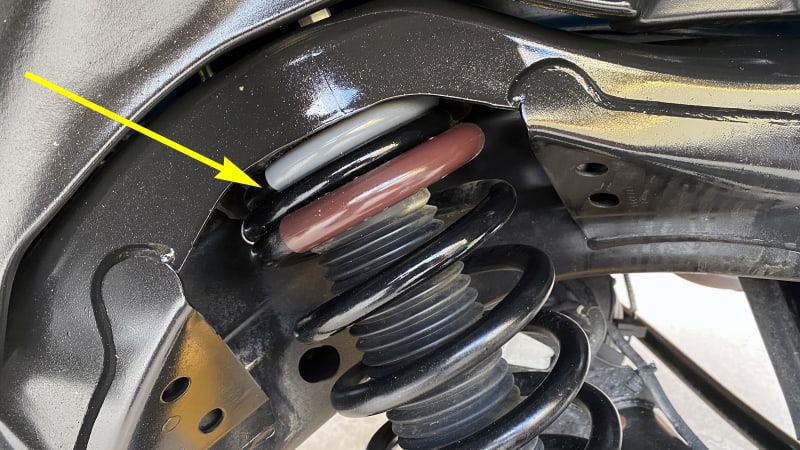

The front bump stop (yellow) is a urethane bumper that sits at the top end of the coil-over spring and damper assembly. Ford uses this design instead of the frame-mounted bump-stops we’re used to seeing on a Tacoma or 4Runner because it gives them greater freedom to tweak the available suspension travel using bolt-on parts.

The aluminum upper control arm (green) is canted downward toward the back to generate a helpful dose of anti-dive geometry, and the ball joint is set far back to help generate a healthy dose of caster. Beyond that, the ball-joint seems to be held in place with a circlip that should allow for easy changes or aftermarket upgrades.

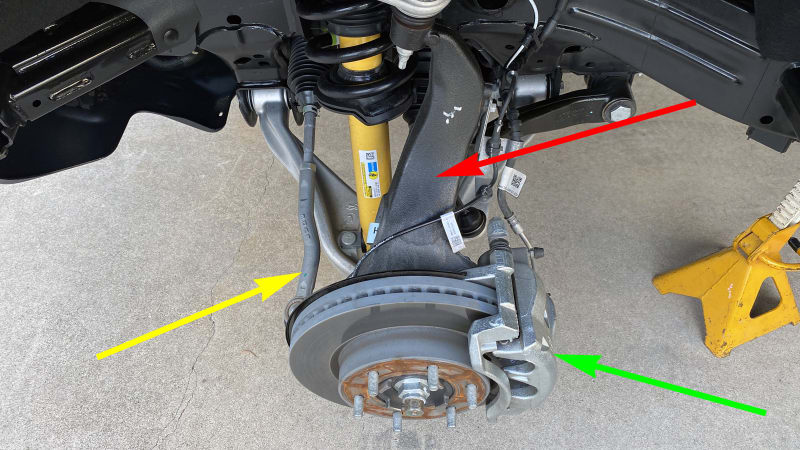

When in place, the tire barely hides the upper ball joint that’s just peeking into this picture. We’re not seeing the extreme high-mount design favored by Toyota, but the front knuckle (red) is still quite tall, a move that reduces upper ball-joint and wishbone bushing loads by increasing the vertical separation distance from the tire contact patch at the ground.

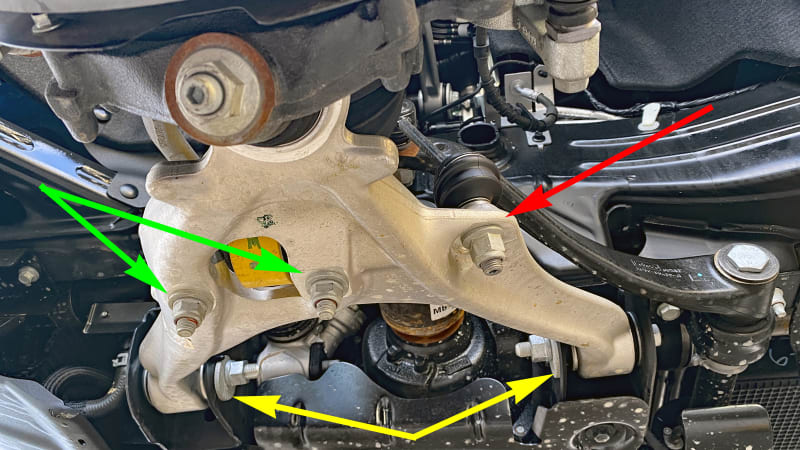

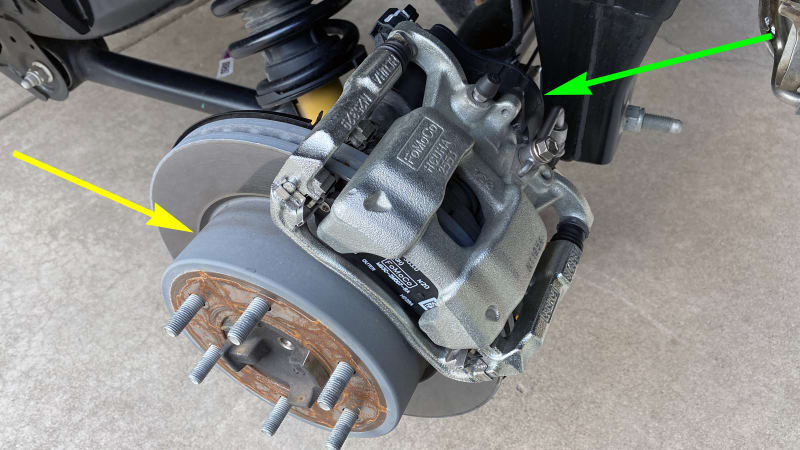

This view also makes it clear that the Bronco has the kind of front-steer rack placement (yellow) we expect to see when an engine is mounted lengthwise, and why the space occupied by the rack-and-pinion steering linkage forces the brake caliper (green) to occupy the unused space on the opposite side.

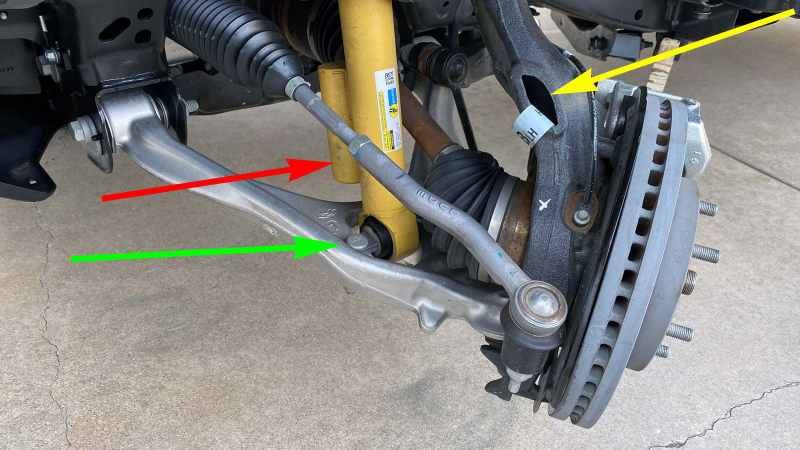

You may have wondered how heavy that steel knuckle (yellow) was going to be, but it’s actually hollow. We’re also getting our first glimpse of how the Bilstein HOSS dampers bolt to the lower wishbone via a lower bushing (green) with a molded-in tie-bar. These dampers have piggyback remote reservoirs (red), and if we could peer inside we’d see stiffer end-travel damping zones at the extreme top and bottom ends of the shock to guard against topping and bottoming.

The lower wishbone and knuckle have protuberances (yellow) that work together as a steering limit stop to keep the steering rack from loading up against its internal end-stop. The other thing to notice is how the knuckle’s thickness is locally optimized (green) to save further weight beyond what they’ve achieved by making the upper section hollow.

Each leg of the wishbone has eccentric cams (yellow) that allow for caster and camber adjustment, and further out we can see the nuts (green) that hold the damper in place. Meanwhile, the stabilizer bar end-link (red) connects to the rear leg of the wishbone.

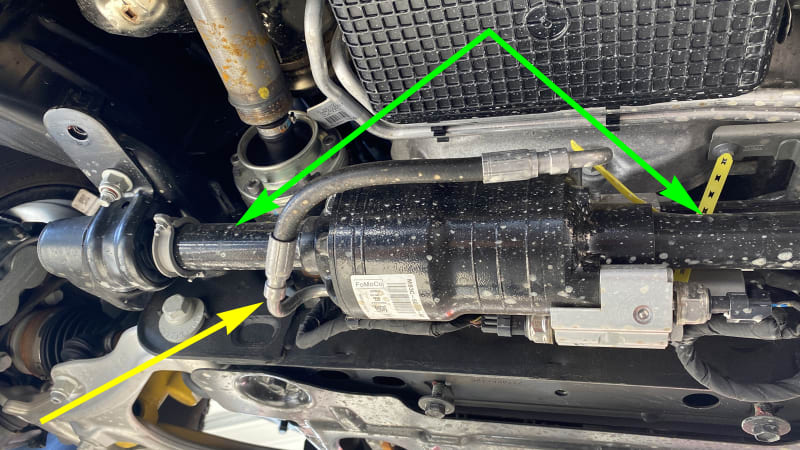

The stabilizer linkage connects to a weird-looking stabilizer bar arm (yellow). We’re used to seeing stabilizer bars made from a simple bent piece of round-stock, but this one consists of a blade that’s bolted (green) and indexed to a separate crosspiece, as you might see in a racecar.

That crosspiece incorporates the First Edition and Badlands’ stabilizer bar disconnect mechanism (yellow), which is both hidden and protected by a stout bash plate. I rather doubt we’d see this bolt-on arm construction on Broncos that lack the stabilizer bar disconnect, but their single-piece fixed bars would mount to the same bushing locations.

It’s a lot easier to see the works with the bash plate removed. The business end of the bar consists of two halves (green) that meet inside a hydraulic coupling mechanism (yellow) that can be disconnected under load. This represents a huge advantage over the Wrangler’s mechanism, which can only be operated on flat ground in no-load conditions.

The Ford unit can be disengaged in H4 or L4 drive modes, and it will automatically reconnect if your speed increases to the point where the bar is needed for safety. But it doesn’t switch fully off at such times – it instead goes into a standby mode that waits to automatically disengage again when your speed drops below the threshold.

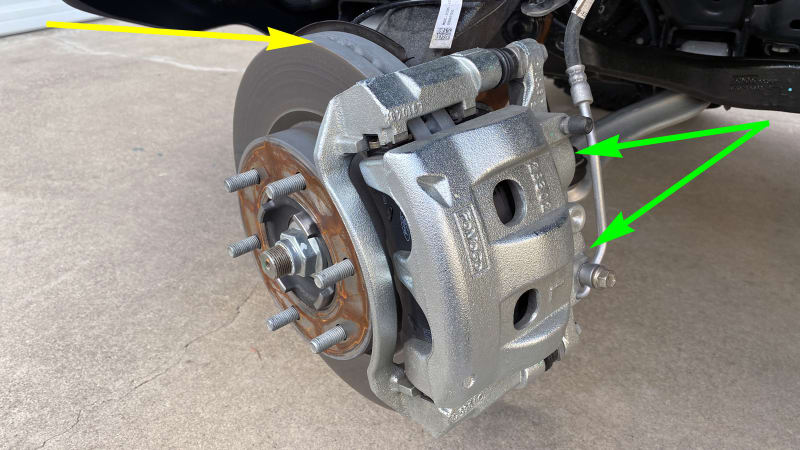

The diameter of the brake rotors (yellow) is fairly modest because the base Bronco comes with 16-inch wheels. But the rotors make up for this by being quite thick, which gives them a lot of thermal mass. The calipers themselves are fairly beefy twin-piston (green) sliding units with sizable brake pads.

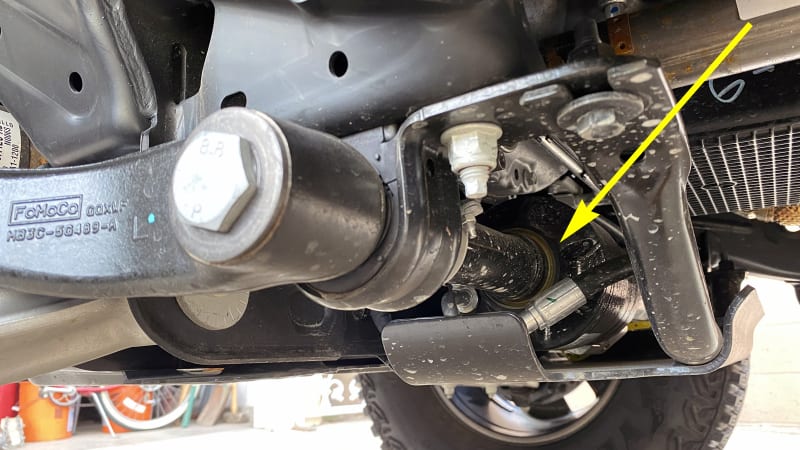

From here, the rear suspension looks incomplete. It is a five-link solid-axle setup, but we can only make out the lower trailing link (yellow).

The coli-over spring and shock assembly bolts into a heavily reinforced pocket (yellow) that’s incorporated into the frame rail.

The coil spring itself employs a dual-rate design, but the initial rate is set up to collapse fully (yellow) when the vehicle is sitting on the ground. For all intents and purposes, the main working area of the spring appears to be a linear rate – unless there are subtle wire diameter variations that aren’t immediately obvious.

Here the suspension is fully unloaded on my Flex Index ramp, and you can see how that initial section has opened up. Its main purpose is to keep the spring seated at full droop, much like the thin tender springs you often see at the top of racing coil-overs.

This view also gives us a sneak-peek at the urethane bump stop (yellow) that sits at the top end of the coil-over assembly. Like the front, the Bronco exclusively employs shock-mounted bump stops. You won’t see a stopper that registers on the solid axle housing itself.

You have to crawl underneath pretty far to get a good view of the upper tailing link (yellow), but it is there.

The upper link’s axle attachment bracket (yellow) is canted forward. That fitting just outside (green) is an axle breather tube that wends its way upwards to keep water out of the differential housing at maximum fording depth.

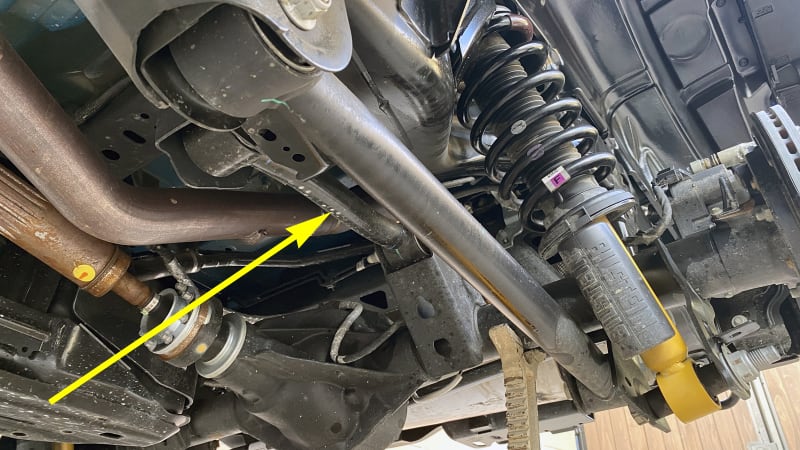

At first I thought the rear link bracketry was low and vulnerable, but it’s really not any lower than the gas tank skid plate (yellow) in the background. Meanwhile, the piggyback-style remote reservoir (green) on the rear Bilstien damper is protected by an impact-resistant stone guard.

We can account for four of the five links because we’ve seen the upper and lower trailing links, and there are two per side. This Panhard bar (aka track rod) is number five. Its fixed end (yellow) attaches to a bracket that’s welded to the frame, while the moving end (green) is bolted to a bracket on the axle housing. It’s about as long as it can be in the available space, and it sits nearly level when the vehicle is on the ground. Both tactics are necessary to minimize the amount of left-right axle shifting that would otherwise occur as the bar swings through an arc as the suspension moves up and down.

The other thing to notice here is what you’re not seeing: a rear stabilizer bar. The Bronco doesn’t have one. Well, this two-door doesn’t. I have not stuck my head under a four-door yet. I imagine it’s the same, because I don’t see any unused brackets.

Like the front, the sizing of the rear brake rotor and caliper setup is limited to what can fit inside the base model’s 16-inch wheels. Still, the rotors are thick and nicely ventilated. The rotor’s deep hat section (yellow) may give you the impression it’s hiding a shoe-type parking brake, but the single-piston sliding caliper has an electronic parking brake (green) bolted onto the back.

The 17-inch wheels that come with the 35-inch LT315/70R17 Sasquatch tires are beadlock capable, which means you can unbolt the decorative 12-bolt ring you see here and replace it with an accessory 24-bolt ring that actually clamps the tire bead in place for extreme low-pressure aired-down off-road running. The same sort of beadlock-capable 17-inch rims also come with the 33-inch Badlands setup.

These are, in fact, Goodyear Wrangler Territory MT tires, but Ford didn’t want the word Wrangler on the Bronco, for obvious reasons. Instead, they invited Goodyear to stamp their name on twice.

Look closely and you’ll see that the decorative 12-bolt beadlock rings aren’t doing any bead locking. They do help add up to a tire assembly weight of some 89 pounds, though. Lift with your knees, is all I’m saying.

The Bronco’s suspension execution is mighty impressive, and I think it gives buyers a great third option that sits about midway between the Jeep Wrangler on one end and the Toyota 4Runner on the other. You get the removable top and doors of the Wrangler, but the Ford’s suspension layout has the same daily-drive benefits of a 4Runner thanks to double wishbone independent front suspension and rack-and-pinion steering. Beyond that, the Bronco benefits from a wider stance and beefy high-flying design that’s based on the Ranger Raptor. Sure, the Jeep Wrangler will flex more in extreme conditions, but the Bronco is no slouch, and it will steer, ride and handle better just about anywhere else.

Contributing writer Dan Edmunds is a veteran automotive engineer and journalist. He worked as a vehicle development engineer for Toyota and Hyundai with an emphasis on chassis tuning, and was the director of vehicle testing at Edmunds.com (no relation) for 14 years.

You can find all of his Suspension Deep Dives here on Autoblog.

Source: www.autoblog.com