Israeli technology firm REE Automotive wants to put the skateboard back into the skateboard EV chassis. You’ve probably heard the term. It describes the multi-use battery-electric platforms from EV makers like Rivian, Canoo, Volkswagen and GM, the promise of the concept being that a single battery-based platform can support a range of vehicles far more easily and more cost-effectively than internal-combustion-engine architecture.

But “skateboard” doesn’t mean what it used to — at least not when it comes to vehicles (skateboarders, you’re still cool). Today’s skateboard chassis aren’t flat and they incorporate structural components like subframes and suspensions. That means that for Volkswagen to turn its ID.3 subcompact hatch into the ID.4 crossover, or Rivian to turn its R1T pickup into the R1S SUV, those companies needed to reengineer their central platforms. And that means EV makers cannot extract the full flexibility and cost savings that a true skateboard chassis promises.

REE co-founder and CEO Daniel Barel said that his company’s been working since 2013 on a platform “that would be so modular and so scalable that everybody would be able to use it as the basis of the vehicles that they want to build.”

.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }

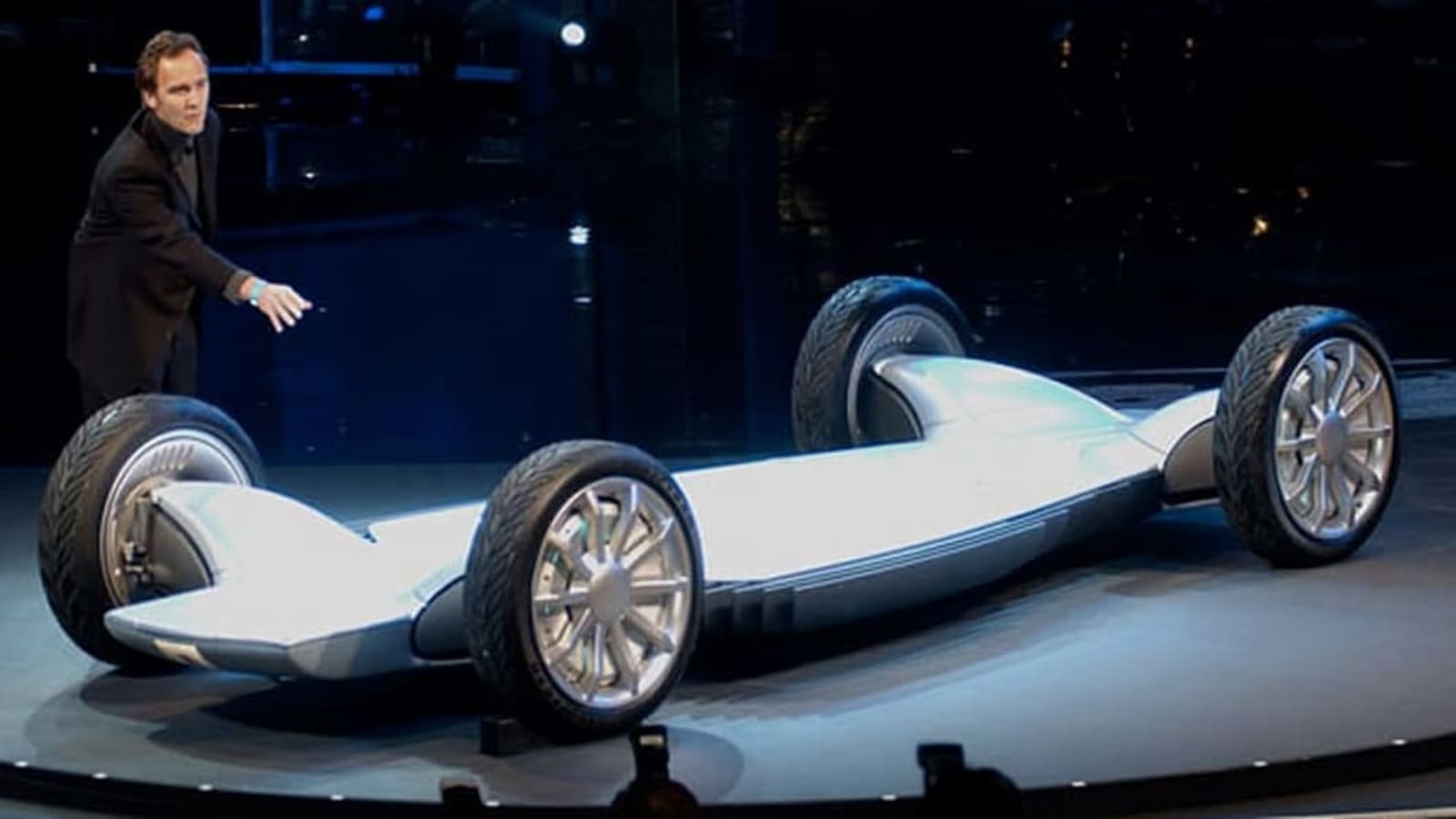

To help understand how far the terminology has strayed and what’s been lost, it’s best to go back almost 20 years to the 2002 North American International Auto Show, when General Motors unveiled its AUTOnomy concept. That is the platform credited with coining the term “skateboard chassis.” It was a six-inch-thick deck, flat and shapely from front to back, contained hydrogen fuel cell innards. GM never explained where the suspension lived, but hub motors powered the four wheels, and a software brain managed drive-, steer-, and brake-by-wire.

Rick Wagoner, GM CEO at the time, saw AUTOnomy as “potentially the start of a revolution in how automobiles are designed, built, and used.” The concept promised more than the body-agnostic platform we call a skateboard chassis today, because — here’s the crucial part — it could fit different bodies and serve different purposes without redesigning the platform.

While REE doesn’t have a connection to GM, its platform resurrects the ghost of that AUTOnomy concept by being a pancake-flat deck from stem to stern containing batteries; power electronics; the AI brain that controls drive-, steer-, and brake-by-wire controls; and a GPS unit.

The billion-dollar AUTOnomy skateboard.

All the bits that make a REE vehicle go — the electric motors, power electronics, gearbox, steering gears, and suspension — are bolted to the corners of the deck inside four discrete modules called REEcorners. A stubby axle extends from the module to support a hub and wheel, steering linkage, brake rotor, and brake caliper, which are the only unsprung masses.

If we’re using an actual skateboard for comparison, REE’s central slab is the skateboard deck; the REEcorner modules are the skateboard’s axle carriers (called trucks on a skateboard) and wheels. And just like one can swap the trucks and wheels of a skateboard without needing to redesign any of the components, REE can combine REEcorner modules to create any combination of front-, rear-, or all-wheel drive vehicles with front-, rear-, or all-wheel steering, without reengineering the deck.

According to Barel, transitioning a REE platform from a Class 3 vehicle with a gross vehicle weight rating (GVWR) of 14,000 pounds (equivalent to a Ford F-350) to a Class 1, with a GVWR of 6000 pounds (a Ford Ranger), or vice-versa, means no more than swapping to the REEcorner modules created for the appropriate vehicle type. There’s no reengineering of the deck, and it takes about 60 minutes to switch modules—roughly 15 minutes to get a new unit bolted on, 45 minutes to deal with the high-voltage system and wheel alignment.

.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }

The chassis steps go from REE’s P1 platform, designed for last-mile deliveries and a maximum payload rating of 772 pounds, to the P7, capable of carrying 11,023 pounds — roughly a Class 6 Medium truck like the Ford F-650. The middle child P4 platform compares with a Mercedes-Benz Sprinter — the kind favored by Amazon — and comes with a payload rating of 1,300 kg (2,866 pounds). Volume-wise, Barel said the P4 has a slightly smaller footprint than a Sprinter, but could have 20 percent more volume. Those benefits come in addition to providing buyers a custom-designed vehicle.

REE will make only its platform and propulsion systems, and assemble the final product. Among its partnerships, REE has signed a preliminary agreement with Indian conglomerate Mahindra to manufacture the rest of the vehicle — like the body and interior — designed according to the client’s needs. Mahindra would also carry out homologation for global markets, but Ree would assemble the vehicles in a local-market integration center.

The plan is to manufacture the subcomponents for vehicle kits. Then those kits will be assembled at REE facilities, called “integration centers,” in the market where the vehicle will be used. The company plans 15 such centers at the moment, the first one in the U.S. slated to open this year.

Because REE is initially focusing on delivery vehicles, it won’t have to worry about extending battery range. But the deck could theoretically fit more batteries, since it omits equipment between the wheels. Asked about the safety of the design, Ree said it “takes into consideration crumple zones, makes use of skid plates and ensures sufficient clearance from the ends of chassis to the battery to meet all necessary requirements,” whether as a commercial or passenger vehicle.

Barel believes the simplicity of the system could pay off on the maintenance side of the ledger as well. Because traditional vehicles contain a wide variety of components, fleet operators often maintain large inventories of various parts. “Why do that?” Barel said. “It takes less than 60 minutes to replace a REEcorner with a brand new corner. There’s no more repairs. There’s nothing. Put it up, replace the corner, put the vehicle back to work, send us back the corner, we’ll fix it for you and send it back to you.” That would save money on parts, warehousing to store parts, and training fleet mechanics.

A fleet operator would need to stock only the REEcorner modules it needs for its vehicles. REE plans to set up a network of facilities where a vehicle owner could drive in to have a module swapped, as well as a network of depots where an owner could send a REEcorner to be fixed.

REE recently joined the list of electric vehicle outfits that have merged with venture capital firms in order to complete an IPO and get their stocks listed on Wall Street. Assuming a successful public offering, a portion of the financial windfall will be invested into an engineering center in the UK where REE will design, test, validate, and homologate its platforms. On top of that, so far this year Ree has signed collaboration deals with Magna, truck-maker Hino, American Axle, and announced Austin, Texas, as the site of its U.S. headquarters and first integration center.

Beyond GM’s Hy-wire concept, which sat on GM’s AUTOnomy chassis and was shown in late 2002, GM never followed through with its innovative idea. If Ree’s platform backs up Barel’s claims — ultimate modularity and ease of repair combined with lower costs, mass-produced for global markets — the tech firm would be the first to unlock the 19-year-old promise of the true skateboard chassis.